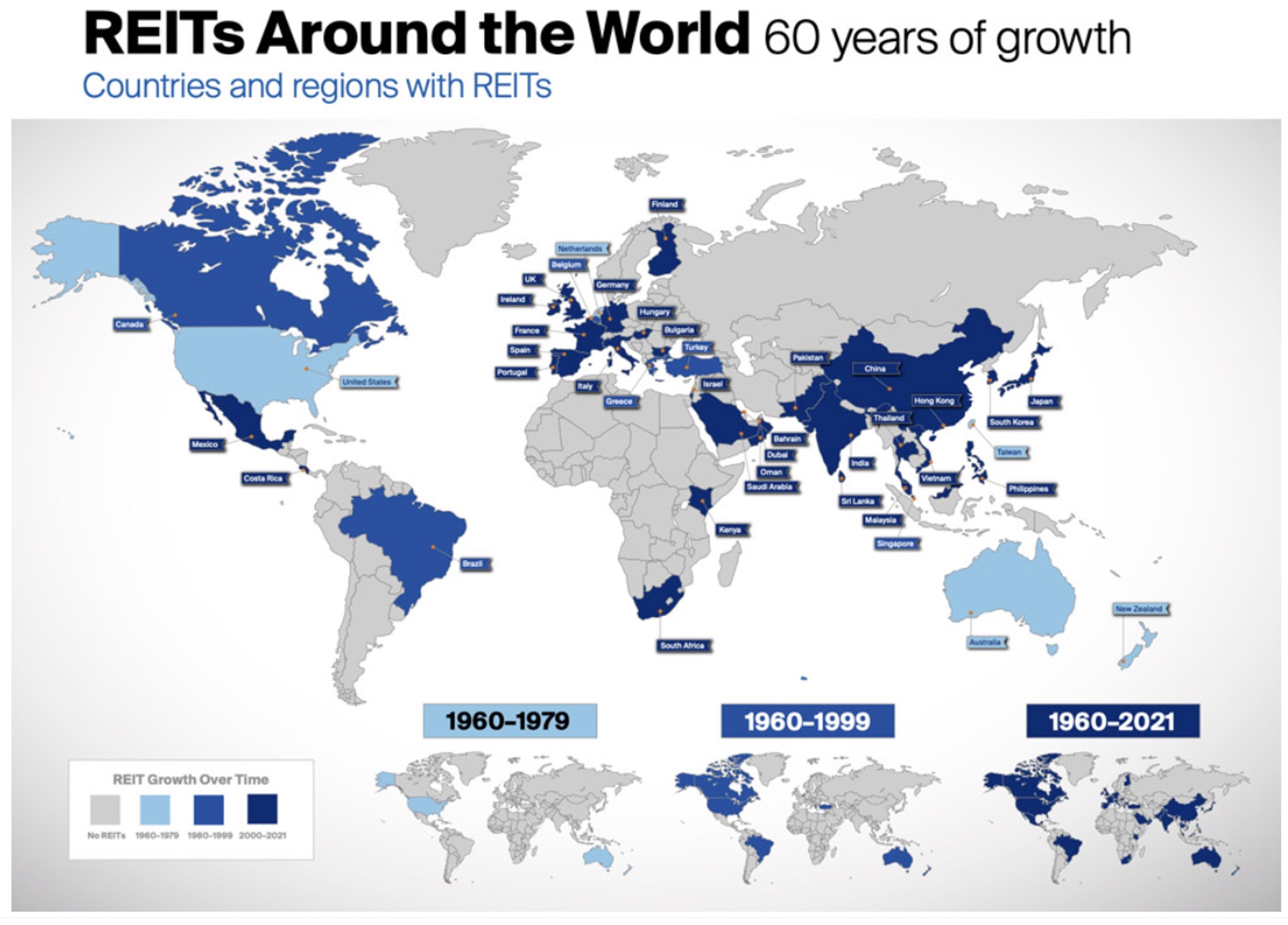

When the U.S. legalized real estate investment trusts in 1960, it was a game-changing notion, and not just for the nation. While it was American business that got the ball rolling and the U.S. Congress that eventually approved the concept…

The implications were far-reaching.

For a much more in-depth rundown of REITs in the U.S., make sure to check out our “What Is a REIT” page. At the end of it, you’ll find a link to the equally informative “How to Play It” page, which links to even further educational pages from there.

This page, however, focuses on international REITs.

Slowly but surely, or in fits and starts, nations around the globe are realizing the citizen-building, economic-driving, tax-revenue-generating force that REITs can be. Today, there are over 40 countries and provinces that have enacted their own real estate investment trust programs (or something very similar).

We’re confident more will follow.

Admittedly, the range of legal requirements and results do vary from country to country. Some legislators hit it out of the park, as evidenced by their thriving REIT markets. Others are criticized by both internal and global investors for their unreasonable rules and regulations.

So if you’re going to buy into them, be sure to do your proper research. The information you’ll find below is just the tip of the REIT iceberg!

A Fast-Paced Trip Around the Rest of the REIT-Filled World

(Source: Nareit, February 2022)

In alphabetical order, the countries that have legislated REITs or allow something similar are…

Argentina: (1995) Fideicomisos financieros inmobiliarios, translated as real estate trusts, don’t offer the typical tax benefits. They’re not very popular as a result, though one or two do manage to exist. These companies do offer other advantages, such as cost reduction, asset protection, and rights negotiations.

Argentina: (1995) Fideicomisos financieros inmobiliarios, translated as real estate trusts, don’t offer the typical tax benefits. They’re not very popular as a result, though one or two do manage to exist. These companies do offer other advantages, such as cost reduction, asset protection, and rights negotiations.

Australia: (1985) A-REITs have three exchanges they can list on: the Bendigo Stock Exchange, Newcastle Stock Exchange, or Australia Pacific Exchange. They’re mostly externally managed but don’t operate under the many set rules other national programs implement. A-REITs offer units instead of shares.

Australia: (1985) A-REITs have three exchanges they can list on: the Bendigo Stock Exchange, Newcastle Stock Exchange, or Australia Pacific Exchange. They’re mostly externally managed but don’t operate under the many set rules other national programs implement. A-REITs offer units instead of shares.

Bahrain: (2015) These REITs pay out at least 90% of their net realized income to unitholders and must be both authorized and regulated by the Central Bank of Bahrain. Bahrain’s only officially licensed stock exchange, the Bahrain Bourse, states that “unitholders can expect to receive stable distributions.”

Bahrain: (2015) These REITs pay out at least 90% of their net realized income to unitholders and must be both authorized and regulated by the Central Bank of Bahrain. Bahrain’s only officially licensed stock exchange, the Bahrain Bourse, states that “unitholders can expect to receive stable distributions.”

Belgium: (1995) BE-REITs, which were restructured in 2014, must distribute just 80% of their post-debt reduction, non-capital gains-specific income. They still enjoy specific tax measures with added government incentives meant to foster the industry. BE-REITs pay dividends annually.

Belgium: (1995) BE-REITs, which were restructured in 2014, must distribute just 80% of their post-debt reduction, non-capital gains-specific income. They still enjoy specific tax measures with added government incentives meant to foster the industry. BE-REITs pay dividends annually.

Brazil: (1993) Fundo de investimento imobiliário, or FII, are traded in units. They must have financial institutions manage them, and construction companies can’t own more than 25% interest in any one REIT. FII distributes at least 95% of their capital gains and operating earnings bi-annually.

Brazil: (1993) Fundo de investimento imobiliário, or FII, are traded in units. They must have financial institutions manage them, and construction companies can’t own more than 25% interest in any one REIT. FII distributes at least 95% of their capital gains and operating earnings bi-annually.

Bulgaria: (2004) Bulgaria’s REITs, known as SPICs, legally exist as special purpose investment companies, a concept that was revamped in 2021. Nationalistic in nature, they must be headquartered in the country and can only own properties within it. SPICs distribute at least 90% of their net profits annually.

Bulgaria: (2004) Bulgaria’s REITs, known as SPICs, legally exist as special purpose investment companies, a concept that was revamped in 2021. Nationalistic in nature, they must be headquartered in the country and can only own properties within it. SPICs distribute at least 90% of their net profits annually.

Canada: (1994) Canadian REITs are legally listed as mutual fund trusts, whereas U.S. REITs are corporations. Canadian REITs also have less institutional support than U.S. REITs and often operate with more leverage. They pay shareholders 100% of their taxable income in dividends on a monthly basis.

Canada: (1994) Canadian REITs are legally listed as mutual fund trusts, whereas U.S. REITs are corporations. Canadian REITs also have less institutional support than U.S. REITs and often operate with more leverage. They pay shareholders 100% of their taxable income in dividends on a monthly basis.

Chile: (2014) Chile offers public investment funds (FI) and private investment funds (FIP) through its REIT program. There are definite structural differences between the two, but both are considered non-taxpayer entities and must pay at least 30% of their annual profits in dividends on an annual basis.

Chile: (2014) Chile offers public investment funds (FI) and private investment funds (FIP) through its REIT program. There are definite structural differences between the two, but both are considered non-taxpayer entities and must pay at least 30% of their annual profits in dividends on an annual basis.

China: (2020) China began considering its C-REIT plan in 2001 and is still experimenting with the concept today. As such, concrete rules do not exist yet, which makes it somewhat of an unknown category. With that said, the sector has been expanding quickly since late 2022, when the first C-REITs launched.

China: (2020) China began considering its C-REIT plan in 2001 and is still experimenting with the concept today. As such, concrete rules do not exist yet, which makes it somewhat of an unknown category. With that said, the sector has been expanding quickly since late 2022, when the first C-REITs launched.

Costa Rica: (1997) While REITs don’t exist in Costa Rica, real estate investment funds (REIFs) and real estate development investment funds (REDIFs) do. Both invest in real estate and real estate-related opportunities with the specific purpose of producing high fixed returns through long-term leases.

Costa Rica: (1997) While REITs don’t exist in Costa Rica, real estate investment funds (REIFs) and real estate development investment funds (REDIFs) do. Both invest in real estate and real estate-related opportunities with the specific purpose of producing high fixed returns through long-term leases.

Dubai: (2006) Few public REITs operate in Dubai, but those that do must be listed on an approved exchange, borrow no more than 70% of their net asset value, and distribute no less than 80% of their annual net income. The Islamic REITs it allows have to further abide under a Shariah Supervisory Board.

Dubai: (2006) Few public REITs operate in Dubai, but those that do must be listed on an approved exchange, borrow no more than 70% of their net asset value, and distribute no less than 80% of their annual net income. The Islamic REITs it allows have to further abide under a Shariah Supervisory Board.

Finland: (2010) Finnish REITs distribute 90% of their funds to shareholders, with each stockholder allowed to hold a maximum of 10% of outstanding shares. No single shareholder can own 11% or more of the business. Despite being established in 2010, no actual Finnish REITs exist at last check.

Finland: (2010) Finnish REITs distribute 90% of their funds to shareholders, with each stockholder allowed to hold a maximum of 10% of outstanding shares. No single shareholder can own 11% or more of the business. Despite being established in 2010, no actual Finnish REITs exist at last check.

France: (2003) Société d‘investissement immobilier cotée, or SICCS, are a bright real estate spot compared to the heavy taxes most other French real estate is subject to. To qualify, SICCS must pay 95% of their rent-specific profit to shareholders and 70% of their profits from realized capital gains.

France: (2003) Société d‘investissement immobilier cotée, or SICCS, are a bright real estate spot compared to the heavy taxes most other French real estate is subject to. To qualify, SICCS must pay 95% of their rent-specific profit to shareholders and 70% of their profits from realized capital gains.

Germany: (2007) G-REITs are easy to identify since they must have “REIT” somewhere in their company name. They pay a minimum of 90% of their distributable profits to shareholders. And at least 75% of equity REITs’ assets have to be actual properties. Critics say G-REITs are too heavily restricted to thrive.

Germany: (2007) G-REITs are easy to identify since they must have “REIT” somewhere in their company name. They pay a minimum of 90% of their distributable profits to shareholders. And at least 75% of equity REITs’ assets have to be actual properties. Critics say G-REITs are too heavily restricted to thrive.

Greece: (1999) The original law created for Greek real estate investment companies (REICs) did not impress qualified businesses, so legislators amended it repeatedly over the years. As they stand today, at least 80% of REICs’ assets must be in real estate in Greece itself or the larger European Economic Area.

Greece: (1999) The original law created for Greek real estate investment companies (REICs) did not impress qualified businesses, so legislators amended it repeatedly over the years. As they stand today, at least 80% of REICs’ assets must be in real estate in Greece itself or the larger European Economic Area.

Hong Kong: (2003) HK-REITs have also undergone many changes over the years and could see more still. They’re externally managed, must hold properties for at least two years unless they provide proof their shareholders would otherwise suffer, and pay out the typical 90% or more of their net profits.

Hong Kong: (2003) HK-REITs have also undergone many changes over the years and could see more still. They’re externally managed, must hold properties for at least two years unless they provide proof their shareholders would otherwise suffer, and pay out the typical 90% or more of their net profits.

Hungary: (2011) Hungarian REITs follow the standard 90% payout model, with the stipulation that 70% of their total assets are real estate properties – each of which can’t exceed a 30% share of the company’s total holdings. These REITs are also limited to real estate-based plays if they want to invest externally.

Hungary: (2011) Hungarian REITs follow the standard 90% payout model, with the stipulation that 70% of their total assets are real estate properties – each of which can’t exceed a 30% share of the company’s total holdings. These REITs are also limited to real estate-based plays if they want to invest externally.

India: (2014) Indian REITs – which can include equity, mortgage, and hybrid models, as well as private, public, and public non-listed – must have unaffiliated trustees, sponsors, and managers. Investors have to pay a minimum of 10,000 rupees (about $1,200) to qualify, but that’s down from the original 50,000.

India: (2014) Indian REITs – which can include equity, mortgage, and hybrid models, as well as private, public, and public non-listed – must have unaffiliated trustees, sponsors, and managers. Investors have to pay a minimum of 10,000 rupees (about $1,200) to qualify, but that’s down from the original 50,000.

Indonesia: (2007) Real estate investment funds, or DIREs, can be Sharia-specific or conventional. The former get 90% or more of their income from Sharia-observing activities. Neither can invest in international real estate or real estate-related assets, or any vacant land or property under development.

Indonesia: (2007) Real estate investment funds, or DIREs, can be Sharia-specific or conventional. The former get 90% or more of their income from Sharia-observing activities. Neither can invest in international real estate or real estate-related assets, or any vacant land or property under development.

Ireland: (2013) Irish REITs depart from the normal payout ratio at 85%. Three-quarters of their aggregate income and market value must come from rental properties. And they must maintain a loan-to-market value of 50% or less. They can own non-Irish properties but need to be listed on an E.U. stock exchange.

Ireland: (2013) Irish REITs depart from the normal payout ratio at 85%. Three-quarters of their aggregate income and market value must come from rental properties. And they must maintain a loan-to-market value of 50% or less. They can own non-Irish properties but need to be listed on an E.U. stock exchange.

Israel: (2006) REITs here are nationally incorporated, controlled, and managed, and only invest in Israeli properties (although their subsidiaries can be internationally based). Israeli REITs pay out their dividends annually from the standard 90% of their chargeable income, and 75% of their assets must be profitable.

Israel: (2006) REITs here are nationally incorporated, controlled, and managed, and only invest in Israeli properties (although their subsidiaries can be internationally based). Israeli REITs pay out their dividends annually from the standard 90% of their chargeable income, and 75% of their assets must be profitable.

Italy: (2007) Societá d’investimento immobiliare quotate, or SIIQ, pay the standard 90% of their taxable income in dividends. They’re required to invest 75% of their capital in real estate, cash, or government bonds. And 75% of their income must come from rent, mortgage interest, and property sales.

Italy: (2007) Societá d’investimento immobiliare quotate, or SIIQ, pay the standard 90% of their taxable income in dividends. They’re required to invest 75% of their capital in real estate, cash, or government bonds. And 75% of their income must come from rent, mortgage interest, and property sales.

Japan: (2000) J-REITs trade-in units but pay dividends just like shares, giving 90% of their distributable profits to investors. They can be taxed unless they meet a list of requirements, and all of them are externally managed. Dozens of J-REITs exist, many of which focus on leasing out office buildings.

Japan: (2000) J-REITs trade-in units but pay dividends just like shares, giving 90% of their distributable profits to investors. They can be taxed unless they meet a list of requirements, and all of them are externally managed. Dozens of J-REITs exist, many of which focus on leasing out office buildings.

Kenya: (2013) Kenyan REITs are regulated via the Capital Markets Authority (CMA) under the 2013 Capital Markets Regulations. This allows for development and construction, or D-REITs; income, or I-REITs; and Islamic REITs. All three involve a trustee buying real estate assets overseen by a manager.

Kenya: (2013) Kenyan REITs are regulated via the Capital Markets Authority (CMA) under the 2013 Capital Markets Regulations. This allows for development and construction, or D-REITs; income, or I-REITs; and Islamic REITs. All three involve a trustee buying real estate assets overseen by a manager.

Lithuania: (2008) Lithuania’s REITs came into existence in three stages, starting with an allowance for REITs designed for non-professional investors. In June 2013, they were allowed for informed investors and, the following month, for professionals. There are varying rules and regulations for each category.

Lithuania: (2008) Lithuania’s REITs came into existence in three stages, starting with an allowance for REITs designed for non-professional investors. In June 2013, they were allowed for informed investors and, the following month, for professionals. There are varying rules and regulations for each category.

Luxembourg: (2007) While the country hasn’t legalized REITs yet, it does allow specialized investment funds, or SIFs, which paved the way for specialized property funds. However, they’re usually restricted to institutional or professional investors. The government is reportedly talking about allowing actual REITs.

Luxembourg: (2007) While the country hasn’t legalized REITs yet, it does allow specialized investment funds, or SIFs, which paved the way for specialized property funds. However, they’re usually restricted to institutional or professional investors. The government is reportedly talking about allowing actual REITs.

Malaysia: (2002) Malaysia, the first Asian country to adopt REITs, calls them property trust funds, a grouping it modifies often – sometimes every year. This ever-changing legality hasn’t stifled real estate companies from signing up, however. There were 18 property trust funds in existence as of 2022.

Malaysia: (2002) Malaysia, the first Asian country to adopt REITs, calls them property trust funds, a grouping it modifies often – sometimes every year. This ever-changing legality hasn’t stifled real estate companies from signing up, however. There were 18 property trust funds in existence as of 2022.

Mexico: (2004) Mexican fideicomisos de inversíon de bienes raíces, or FIBRAs, must pay out at least 95% of their taxable income. As is often the case, 70% of their funds must be invested in real estate. But, uniquely, they must hold onto properties – whether built or bought – for a full four years before selling.

Mexico: (2004) Mexican fideicomisos de inversíon de bienes raíces, or FIBRAs, must pay out at least 95% of their taxable income. As is often the case, 70% of their funds must be invested in real estate. But, uniquely, they must hold onto properties – whether built or bought – for a full four years before selling.

Netherlands: (1969) Fiscale beleggingsinstellingen, or FBIs, pay out 100% of their taxable profits. They’re restricted to investing in passive portfolio investments but are allowed to hold properties outside of the Netherlands. An FBI’s debt can’t exceed 60% of the tax book value of the real estate assets they hold.

Netherlands: (1969) Fiscale beleggingsinstellingen, or FBIs, pay out 100% of their taxable profits. They’re restricted to investing in passive portfolio investments but are allowed to hold properties outside of the Netherlands. An FBI’s debt can’t exceed 60% of the tax book value of the real estate assets they hold.

New Zealand: (2007) Portfolio investment entities, or PIEs, are a complicated construct that still seems to work well. REITs themselves aren’t legalized in New Zealand, but PIEs operate like them anyway. They can be listed or unlisted, and distribution details are determined on an induvial company basis.

New Zealand: (2007) Portfolio investment entities, or PIEs, are a complicated construct that still seems to work well. REITs themselves aren’t legalized in New Zealand, but PIEs operate like them anyway. They can be listed or unlisted, and distribution details are determined on an induvial company basis.

Nigeria: (2004) Real estate investment schemes, or REIS, must pay out at least 75% of their income to shareholders once a year. They can’t be financial or insurance companies, though mortgage REIS are allowed. So are equity and hybrid varieties. Either way, they must be publicly traded or privately owned.

Nigeria: (2004) Real estate investment schemes, or REIS, must pay out at least 75% of their income to shareholders once a year. They can’t be financial or insurance companies, though mortgage REIS are allowed. So are equity and hybrid varieties. Either way, they must be publicly traded or privately owned.

Oman: (2018) Omani REITs distribute the usual 90% or more of their taxable income to unitholders (not shareholders). They’re prohibited from borrowing more than 60% of their total asset value at any one time unless they can convince their investors to vote for a higher amount in a general meeting.

Oman: (2018) Omani REITs distribute the usual 90% or more of their taxable income to unitholders (not shareholders). They’re prohibited from borrowing more than 60% of their total asset value at any one time unless they can convince their investors to vote for a higher amount in a general meeting.

Pakistan: (2007) Pakistani REITs require a board of trustees over them, as well as an external REIT management company to handle their business. These RMCs must have a 20%-50% stake in the company and can’t charge management fees. Pakistani REITs pay out the standard 90% of their profits.

Philippines: (2009) P-REITs are closely monitored by the government and overseen by boards of mainly Filipino residents. A third of those directors must be independent. Listed on the Philippine Stock Exchange as real estate investment companies, P-REITs keep paid-up capitals of PHP300 million or more.

Philippines: (2009) P-REITs are closely monitored by the government and overseen by boards of mainly Filipino residents. A third of those directors must be independent. Listed on the Philippine Stock Exchange as real estate investment companies, P-REITs keep paid-up capitals of PHP300 million or more.

Portugal: (2019) Sociedades de investimento e gestão imobiliária, or SIGIs, translate as “real estate investment and asset management companies.” These private limited liability companies must have either Sociedades de investimento e gestão imobiliária or SIGI in their name to qualify for tax benefits.

Portugal: (2019) Sociedades de investimento e gestão imobiliária, or SIGIs, translate as “real estate investment and asset management companies.” These private limited liability companies must have either Sociedades de investimento e gestão imobiliária or SIGI in their name to qualify for tax benefits.

Puerto Rico: (1972) Puerto Rico is another one of those countries that has repeatedly rethought its REIT model, most recently in 2020. As-is, a minimum 95% of these companies’ gross income must be from approved sources and 75% from real estate. Shareholders receive 90% of their net taxable income.

Puerto Rico: (1972) Puerto Rico is another one of those countries that has repeatedly rethought its REIT model, most recently in 2020. As-is, a minimum 95% of these companies’ gross income must be from approved sources and 75% from real estate. Shareholders receive 90% of their net taxable income.

Saudi Arabia: (2016) Saudi Arabian REITs abide by significant disclosure requirements and regulations under the Capital Markets Authority, or CMA. They must maintain SAR500 million or more in capital if formed after October 2018. And no more than half of their total asset value can be leveraged.

Saudi Arabia: (2016) Saudi Arabian REITs abide by significant disclosure requirements and regulations under the Capital Markets Authority, or CMA. They must maintain SAR500 million or more in capital if formed after October 2018. And no more than half of their total asset value can be leveraged.

Singapore: (1999) S-REITs, of which there are dozens, are listed on the Singapore Exchange and approved by the government’s Inland Revenue Authority and/or Ministry of Finance. Most are externally managed, though they don’t have to be. And there are no additional restrictions made on foreign unitholders.

Singapore: (1999) S-REITs, of which there are dozens, are listed on the Singapore Exchange and approved by the government’s Inland Revenue Authority and/or Ministry of Finance. Most are externally managed, though they don’t have to be. And there are no additional restrictions made on foreign unitholders.

South Africa: (2013) SA REITs must own R300 million worth of property or more under the watch of a committee, with less than 60% of their gross asset value being leveraged. Rent checks must account for at least 75% of their income, and they must distribute 75% of their taxable earnings to shareholders.

South Africa: (2013) SA REITs must own R300 million worth of property or more under the watch of a committee, with less than 60% of their gross asset value being leveraged. Rent checks must account for at least 75% of their income, and they must distribute 75% of their taxable earnings to shareholders.

South Korea: (2001) South Korean REITs fall into three categories: self-managed (REICs); commissioned, or entrusted management; and corporate restructuring. Each comes with its own rules. The latter two, for instance, are special purpose companies. And corporate restructuring REITs also have limited lives.

South Korea: (2001) South Korean REITs fall into three categories: self-managed (REICs); commissioned, or entrusted management; and corporate restructuring. Each comes with its own rules. The latter two, for instance, are special purpose companies. And corporate restructuring REITs also have limited lives.

Spain: (2009) Sociedades anónimas cotizadas de inversión en el mercado inmobiliario – translated as “listed investment companies in the real estate market” – must have shared capital of at least €5 million and sociedades anónimas cotizadas de inversión en el mercado inmobiliario (or SOCIMI) in their name.

Spain: (2009) Sociedades anónimas cotizadas de inversión en el mercado inmobiliario – translated as “listed investment companies in the real estate market” – must have shared capital of at least €5 million and sociedades anónimas cotizadas de inversión en el mercado inmobiliario (or SOCIMI) in their name.

Taiwan: (2003) Taiwan follows the normal 90% rule for how much of its REITs’ annual income must be paid to shareholders. At least 75% of their assets must be in real estate, with a limited amount allowed to be under development at any one time. They’re also limited in their international investing abilities.

Taiwan: (2003) Taiwan follows the normal 90% rule for how much of its REITs’ annual income must be paid to shareholders. At least 75% of their assets must be in real estate, with a limited amount allowed to be under development at any one time. They’re also limited in their international investing abilities.

Thailand: (2012) Thai REITs can invest in almost all real estate, including overseas, that isn’t tied to illegal or immoral activities. But they’re very limited in holding assets under construction. Investment-grade REITs can’t borrow more than 60% of their total assets, and it’s 35% for the non-investment-grade REITs.

Thailand: (2012) Thai REITs can invest in almost all real estate, including overseas, that isn’t tied to illegal or immoral activities. But they’re very limited in holding assets under construction. Investment-grade REITs can’t borrow more than 60% of their total assets, and it’s 35% for the non-investment-grade REITs.

Turkey: (1995) Turkish real estate investment companies (REICs) pay out annual dividends. They must put 50% or more of their capital into pre-built real estate, limiting their ownership of development projects. REICs have been amended repeatedly over the years, but have remained popular.

Turkey: (1995) Turkish real estate investment companies (REICs) pay out annual dividends. They must put 50% or more of their capital into pre-built real estate, limiting their ownership of development projects. REICs have been amended repeatedly over the years, but have remained popular.

United Kingdom: (2007) UK-REITs cannot own properties outside of the country, must be listed on a national exchange, and need to distribute the typical 90% or more of their taxable income. The laws that govern them keep improving as Parliament keeps looking into ways to promote them to investors.

United Kingdom: (2007) UK-REITs cannot own properties outside of the country, must be listed on a national exchange, and need to distribute the typical 90% or more of their taxable income. The laws that govern them keep improving as Parliament keeps looking into ways to promote them to investors.

Vietnam: (2021) V-REITs first came around in 2010 via a law that’s since been struck down and replaced in 2021. So in one sense, they’re the new kid in town; in another, they’ve been around the block. As-is, 65% or more of their net asset value must be invested in national real estate under specific conditions.

Vietnam: (2021) V-REITs first came around in 2010 via a law that’s since been struck down and replaced in 2021. So in one sense, they’re the new kid in town; in another, they’ve been around the block. As-is, 65% or more of their net asset value must be invested in national real estate under specific conditions.

Further Notes to Know About International REITs

According to Nareit, the world’s largest and most influential REIT advocate, there were 893 REITs listed around the world – including the U.S. – as of the second quarter of 2023. All told, they had a $1.9 trillion equity market cap.

That’s “trillion” with a T.

Not million. Not even billion. Trillion. And going on multi-trillion, at that.

In addition, owning global REITs can help balance out your portfolio to better sustain it (and you) against regional volatility. And, especially in the case of emerging markets, you can own companies with great growth rates that give you high rates of return.

Why wouldn’t you want a piece of that?

Of course, there are reasons to be wary, including (and perhaps especially) the fact that you’re not just putting your hard-earned money into companies you’re not excessively familiar with… these companies also exist within countries or regions you’re not excessively familiar with – if you’re familiar with them at all.

No matter what country you’re in and what country you’re looking into, international investing could (but doesn’t always) include paying additional taxes for non-citizens or non-residents. Corrupt, inept, or otherwise convoluted government rules and regulations can provide further headaches. Currency considerations are another area you’ll need to know about while having little to no control over. And societal expectations can easily contribute to the mix of must-know facts and figures that are difficult to take in.

In other words, there are many risks involved in adding global REITs to your personal portfolio. Perhaps too many uncertainties for some people to actively invest in these international opportunities. But for those who do, we highly recommend at least considering the value of using a trade desk. This way, you’ll be able to find order flows and execute the trades you’re interested in with more confidence.

If you’re truly torn between investing in international REITs and not investing in them, you could also look into the closed-end funds (CEFs), mutual funds, and/or exchange-traded funds (ETFs) that hold them. The latter two asset baskets in particular offer easy and efficient ways for investors to add global listed real estate positions to their portfolios.

Brad’s newest book, REITs for Dummies, details a list of these asset baskets you might want to invest in.