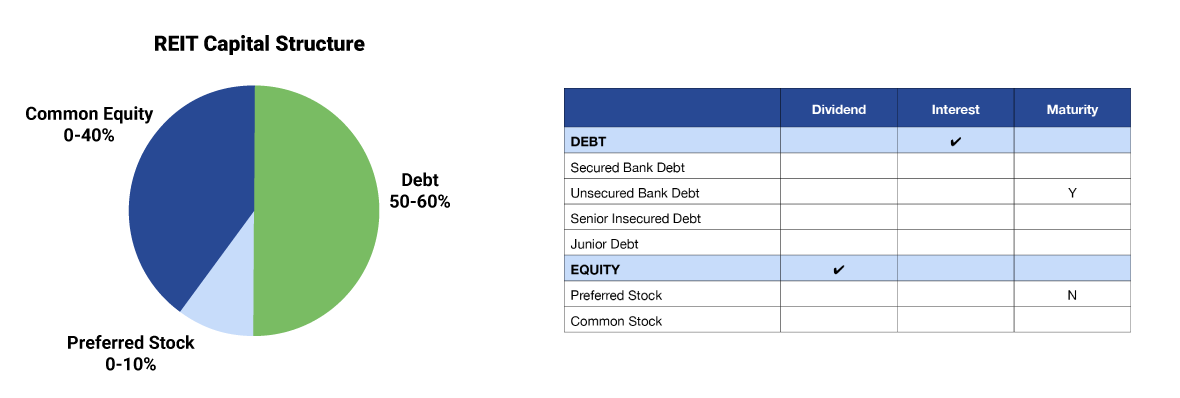

The REIT sector encompasses a variety of investment choices, with many publicly traded REITs offering preferred equity and bonds on top of common equity shares.

Each one has its own pros and cons. And each can be used or combined to create a customized risk-and-return profile for your particular portfolio:

Why Invest in REITs?

The REIT sector encompasses a variety of investment choices, with many publicly traded REITs offering preferred equity and bonds on top of common equity shares.

Each one has its own pros and cons. And each can be used or combined to create a customized risk-and-return profile for your particular portfolio:

Which offering – or combination of them – is best for you? To answer that question, it’s best to first understand the ins and outs of each.

Common Stock

Within a REIT’s capital structure, common stock – also known as equity capital – holds both the highest risk and highest return potential. Investors who choose this route (and most do) share in the company’s profits and losses, as well as the market’s perception about either.

Because of this position, they do get to vote on company picks and policies like electing (or not electing) directors and approving (or rejecting) major actions.

Of course, the fewer shares held, the less impact the vote. But the right exists nonetheless.

As for risks, in case the previous information didn’t already make this clear enough, they’re very real. When push comes to shove, it’s the investors who can lose everything. So they need to focus especially on each company’s fundamentals and business outlook.

Common stock investors intensely lower their chances of losing money and very much increase their chances of success by choosing businesses that are well managed and well positioned, with plenty of cash on hand in case of the unexpected – whether that comes in the form of financial shocks like the 2020 shutdowns or phenomenal investment opportunities that suddenly open up.

Looking at it from the publicly traded company’s standpoint, common stock is a huge advantage one way or the other. It serves as a traditional source for financing, and a very permanent kind at that. After all, and as already stated, there’s no actual obligation to repay it should things go wrong.

This isn’t to say there’s no pressure on the company at all. Only that it’s not legally responsible if its common shareholders lose out.

A worthwhile company with reputable management, of course, will care anyway. A lot. It will work hard to add leverage to its capital structure in order to increase its real estate portfolio and, as a result, the returns to its investors. Which brings us right back to choosing businesses that are well managed and well positioned, with plenty of cash on hand.

Preferred Stock

Preferred stock (or preferred equity) is essentially the shareholders’ equity on a company’s balance sheet. In the case of a company failure, preferred dividends must be paid out before common stock dividends – though after bonds.

Like bonds, preferred stocks offer dividends with rates that are typically stated from the beginning. And they don’t come with voting rights. So while they’re appropriately called “stocks,” they really are something of an “in-between” capital investment, where they’re not completely debt but not completely equity either.

Preferred stock is often attractive to those with low risk tolerance, considering its well-earned (though hardly perfect) reputation for stability. But even more confident investors with largely common-share-focused portfolios can benefit from it. It’s one more way to diversify, adding another layer of protection against market volatility.

Preferred stock dividends have to be approved and declared by each company’s board of directors. And they’re not given the go-ahead lightly. It’s almost always well-managed, well-placed, well-financed conservative companies – REITs or otherwise – that end up offering preferreds.

Again, this doesn’t mean they’re foolproof, only that they’re known for being stable as a general rule.

Incidentally, no maturity date is included, only an optional redemption date – as in optional for the REIT in question to exercise. These dividends keep coming as a pre-established amount until:

-

- The preferred equity is redeemed by the company on or after the optional redemption date.

- The board of directors suspends the dividend until further notice.

- The company goes bankrupt

For the record, those possibilities are listed in order of likelihood, with No. 3 being very unlikely. Companies typically do everything they can to avoid cutting preferred dividends. Otherwise, it would be regarded as a failure on their part and a bad sign of things to come.

In short, failure to pay preferred obligations sends the market a bad signal about the business behind them – the very last thing management wants to do. All the same, it can happen due to:

-

- Interest rate risk – Since preferred stocks have no stated maturity date and the dividend rate is often fixed, a change in interest rates can affect their market price. This is often referred to as duration risk.

- Liquidity risk – Preferred stocks are often not traded in significant volume. This creates the possibility of price volatility when sizable orders are being placed and/or during periods of price discovery.

- Optional redemption risk – After an optional redemption date, a company can redeem a dividend at par. For preferred stocks purchased above par, this can cause a capital loss on the unamortized premium paid

With that said, preferred stocks purchased below par can lead to a capital gain on the accreted discount paid. Either way, this impact is often understood and measured by utilizing the security’s yield-to-call.

When the current equity market is flat to lower – and when interest rate projections are steady – it can make for an excellent buying opportunity.

REIT Bonds

Here at iREIT®, we’re fond of REIT debt in the credit space. That’s because of the financial covenants it typically contains, as well as its attractive spreads.

REIT bonds are typically issued from an operating partnership. They’re also often unconditionally guaranteed, jointly and separately, on a senior unsecured basis by current and future subsidiaries.

It’s always important to know how much debt comes ahead of your bonds in terms of seniority (i.e., who’s going to get paid first in the case of bankruptcy). Fortunately, REIT bonds have some of the best legal contracts, known as covenants, in the investment-grade debt space. And they do a bang-up job reporting on them.

The covenants contained within REIT bonds often focus on the following metrics:

-

- Unencumbered asset coverage of unsecured debt

- Maximum amount of total debt

- Maximum amount of secured debt

- Minimum income coverage of debt service

iREIT® focuses heavily on these financial statements. We want to see strong indications that investors will be protected at all levels of the capital structure by limiting the amount of leverage a REIT can take on… while simultaneously helping to ensure that unsecured assets cover unsecured debt.

For the record, every bond issue comes with a prospectus. And every prospectus is an important piece of any analysis that’s worth reading. This is a resource that shouldn’t be taken for granted.